Cameron Crowe called Double Indemnity "flawless film-making". Woody Allen declared it "the greatest movie ever made". Even if you can't go along with that, there can be no disputing that it is the finest film noir of all time, though it was made in 1944, before the term film noir was even coined.

Adapting James M Cain's 1935 novella about a straight-arrow insurance salesman tempted into murder by a duplicitous housewife, genre-hopping director Billy Wilder recruited Raymond Chandler as co-writer. Chandler, said Wilder, "was a mess, but he could write a beautiful sentence". Noir's visual style, which had its roots in German expressionism, was forged here, though Wilder insisted that he was going for a "newsreel" effect. "We had to be realistic," he said. "You had to believe the situation and the characters, or all was lost."

But the ace in the hole is Barbara Stanwyck as Phyllis Dietrichson, a vision of amorality in a "honey of an anklet" and a platinum wig. She can lower her sunglasses and make it look like the last word in predatory desire. And she's not just a vamp: she's a psychopath. There are few shots in cinema as bone-chilling as the closeup on Stanwyck's face as Neff dispatches Phyllis's husband in the back seat of a car. Miklós Rózsa's fretful strings tell us throughout the picture: beware. Stanwyck had been reluctant to take the role, confessing: "I was a little frightened of it." Wilder asked whether she was an actress or a mouse. When she plumped for the former, he shot back: "Then take the part." Source: www.theguardian.com

Stanwyck made three of her very best films opposite Fred MacMurray: Remember the Night, Double Indemnity, and There’s Always Tomorrow. Her fourth film with MacMurray, a 3-D western called The Moonlighter (1953), has a poor reputation, but it boasts a smart script by Niven Busch, who provided the source material for The Furies, and an effectively dramatic opening.

She stops the car and honks the horn, which is Walter’s cue to strangle the husband. As he does this, Wilder gives Stanwyck a justly famous close-up to show how Phyllis reacts. At first her mouth is open, excitedly, but then it closes again, tightly. In her eyes, there’s a nearly unreadable look. It is at once childlike and sad, and there’s a bit of self-recognition and a bit of satisfaction—and a bit of disappointment that the whole job is over, for she had so enjoyed the planning. “What comes next?” she seems to think, with the melancholy of a serial killer who knows that they can only really get off every once in a great while. There’s even some joy in her face. So many things are blended together in this close-up that it has the visual effect of a full orchestra playing at full blast—probably something by Mahler. Stanwyck takes you through every gradation of what a sociopath like Phyllis feels. -"Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman" (2012) by Dan Callahan

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Barbara Stanwyck's emotional transformations, Break-Up with Robert Taylor

"Barbara Stanwyck (born Ruby Catherine Stevens) was the greatest emotional actress the screen has yet known." —Frank Capra

Barbara Stanwyck and Mae Clarke, 1927, New York

During the making of Big Time, the studio promised Mae Clarke that great things were going to happen to her. Mae and Barbara met for lunch. Mae talked about 'Big Time'. John Ford was in it as himself, a Hollywood director. During the lunch, Mae felt an inexplicable tension from Barbara, that she couldn’t reach her. Mae sat there “with the dearest friend I’ve ever had,” she said. “There was a constraint between us as though we were strangers.” In New York, Mae and Barbara had been inseparable; they’d shared the same bed, eaten together, worked together. Mae couldn’t understand what was wrong. She felt that if she could “just bridge those silences everything would be all right.” There was nothing else to talk about, so Mae talked about the plans the studio had for her. “The picture didn’t mean half as much to me as getting close to Barbara again. But she didn’t understand. “Barbara thought I was getting 'high-hat'. And all I could think of was that Barbara didn’t want to have anything to do with me. I’m a link that binds her to the past. In New York we were harum scarum kids, madcaps, who did crazy things.” -"A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940" (2013) by Victoria Wilson

“Stanwyck was slim, and remained so over her career. Regardless of the obligations and pressures regarding size and shape for women in Hollywood, or her own needs and desires as an actress and a person, or the occasions within the films that show off her body, Stanwyck rarely advertises a superficial fantasy of feminine appearance. She is too busy exploring the subtlety of interactions.” ―Andrew Klevan, author of Barbara Stanwyck (Film Stars), 2013

"Lots of actresses are getting by with good looks and practically nothing else. And there are other actresses who have brains and no beauty," said director William Wellman. "But when you get beauty and brains together, there's no stopping her – and the best example of that is Barbara."

Barbara later described her transformation: “Only through Willard Mack’s kindness in coaching me, showing me all the tricks, how to sell myself by entrances and exits, did I get by. It was Willard Mack who completely disarranged my mental make-up. The process—like all processes of birth and death, I guess—was pretty damn painful. Especially for him. I got temperamental. The truth is, I was scared. I’d storm and yell that I couldn’t act—couldn’t, and what’s more, wouldn’t. I think I can honestly say that this was my first and last flare-up of temperament, because Mr. Mack—who had flattered and encouraged me— shrewdly reversed his tactics.

One day, right before the entire company, he screamed back at me that I was right, I was dead right. I was a chorus girl, would always be a chorus girl, would live and die a chorus girl, so to hell with me. It worked. I yelled back that I could act, would act, was not a chorus girl—was Bernhardt, Fiske and all the Booths and Barrymores rolled into one.”

“Underneath her sullen shyness,” Frank Capra later wrote, “smoldered the emotional fires of a young Duse, or a Bernhardt. Naïve, unsophisticated, caring nothing about make-up, clothes or hairdos, this chorus girl could grab your heart and tear it to pieces … She just turned it on—and everything else on the stage stopped.” 'Ladies of Leisure' was a great hit, a major step up for Columbia, and it made an instant star of Barbara Stanwyck. Critics raved about this lovely young actress, effusively praising the naturalness and honesty of her acting, her unique voice and her strong presence. Photoplay rhapsodized about “the astonishing performance of a little tap-dancing beauty who has in her the spirit of a great artist… Go and be amazed by this Barbara girl.”

David Manners and Barbara Stanwyck in "The Miracle Woman" (1931), based on the play "Bless You, Sister" by John Meehan and Robert Riskin, directed by Frank Capra

She’d become Capra’s favorite actress and he directed her in three more Columbia dramas. 'The Miracle Woman' (1931) was an initially daring but failed attempt at telling the story of a fraudulent preacher, based on the notorious Aimee Semple McPherson. Barbara delivered a strong performance but the cop-out script sank it. 'Forbidden' (’32) was nothing more than mawkish soap opera worthy of neither of them. 'The Bitter Tea of General Yen' (’32) was a truly strange tale with Barbara as the captive and lover of a Chinese warlord, but casting Swedish Nils Asther as General Yen was pure racial cowardice. None approached 'Ladies of Leisure' in quality or box office success. Barbara always considered William Wellman, Frank Capra and Billy Wilder her favorite directors.

Her final 1939 film was Clifford Odets’ 'Golden Boy'. It had been a high-profile hit on Broadway and the movie version was severely marred by a sappy happy ending that was widely criticized, but Barbara was well received for her unflinching portrait of a hard-edged “dame from Newark” who falls for the young hero. The boy, an extremely demanding role, was played by a very nervous newcomer, William Holden.

It didn’t start out too well. When she got word that he was going to be fired, she threatened to walk off the picture if they did any such thing, and spent every available moment coaching and working with him so he could deliver the performance she knew he was capable of. With her help, 'Golden Boy' made William Holden a star, and every year for the rest of his life he sent her flowers on the anniversary of the film’s starting date.

William Holden and Barbara Stanwyck during the 50th Annual Academy Awards at Dorothy Chandler Pavillion in Los Angeles.

Many years later, when Holden and Stanwyck were introduced together as presenters at the 1978 Academy Awards, he unexpectedly ditched their prepared script, saying instead: “Before Barbara and I present this next award, I’d like to say something. Thirty-nine years ago this month we were working in a film together called 'Golden Boy', and it wasn’t going well because I was going to be replaced. But due to this lovely human being and her interest and understanding and her professional integrity and her encouragement and, above all, her generosity, I’m here tonight.” Surprised and overcome, her eyes filled with tears as she embraced him. In the midst of shooting 'Golden Boy', on May 14, 1939, she and Robert Taylor were quietly married.

'Ball of Fire' (1941) solidified her new glamour girl image, her naturally thin upper lip now enlarged and reshaped with artfully flared lipstick. (She retained this lush-lipped look for the next 15 years.) She was Sugarpuss O’Shea, a leggy, bespangled showgirl tootsie on the lam from the cops, hiding out in a houseful of stodgy professors and falling for the youngest of them (Gary Cooper). Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett wrote the delightful script, Howard Hawks directed, and Barbara’s hyper-energetic performance was a critical and popular triumph, earning her another Oscar nomination.

Bad wig or not, 'Double Indemnity' was a smash, and audiences loved seeing Barbara in that sort of role. She scored her third Oscar nomination, but Gaslight’s weepily sympathetic Ingrid Bergman took home the prize.

Paramount’s 'The Strange Love of Martha Ivers' (1946) was a gleeful return to the shady world of noir, her Martha looking gorgeous—no wig this time—as she killed and schemed her way to her own eventual destruction. She now had no reservations about going the limit and her performance was neurotically succulent and corrupt. With her dancer’s grace, economy of movement and venomous eyes, she was certainly by now the most dangerous woman in movies and the poor saps who got tangled in her web paid a fearsome prize. No, it isn’t so pretty what a dame without pity can do. If 'Double Indemnity' started that engine, Martha Ivers put it into overdrive.

In 1951 Barbara divorced Robert Taylor. His infidelities had become common knowledge and her most passionate fidelity had long been to her profession. In 1954 he married German-born actress Ursula Thiess and the following year she gave birth to a son, his first child. Barbara never remarried.

The American Film Institute honored her on April 9, 1987, with AFI’s Salute to Barbara Stanwyck, an all-star tribute to her body of work on film. She had recently thrown her back out and was hospitalized and in considerable pain, but worked out with barbells to be able to be there. A host of her co-stars and admirers lavished their praise, but Billy Wilder topped them all:

“I learned many years ago never to say, ‘This is the best actor or actress I’ve ever worked with,’ because the next time you want a star, he or she is gonna say ‘Wait a minute, you said Stanwyck was the greatest, now what does that make me?’ Always say she’s one of the two greatest stars you’ve worked with and whenever you approach a star, say, ‘You were the one I meant.’ Except, of course, for tonight. I hope nobody’s watching me. She was the best!” When, at the conclusion, Barbara approached the podium to accept accept her award, her response to all the evening’s hosannas was “Honest to God, I can’t walk on water.” In thanking all those who helped her on her journey, she singled out Wilder, “who taught me to kill.” After the evening’s festivities she returned to the hospital.

Rex Reed had once asked her to analyze her stardom or some such folderol, but she didn’t take the bait: “What the hell. Whatever I had, it worked, didn’t it?” -"Barbara Stanwyck: The Furies" (2004) by Ray Hagen from "Killer tomatoes: fifteen tough film dames" by Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner.

"Trusty, dusky, vivid, true, With eyes of gold and brambledew, Steel-true and blade-straight, The great artificer made my mate." —Robert Taylor on Barbara Stanwyck, quoting Robert Louis Stevenson

Ivy Pearson-Mooring would often come over to the Taylor home and do the ironing. Ivy recalls Stanwyck as, “very nice to me, but it was clear that there were problems in their marriage.” Ivy Pearson-Mooring's husband Len Pearson started a business as a valet to the stars. In this capacity he would organize their wardrobe, shine their shoes and press their suits. He soon had a clientele that included Keenan Wynn, Mervyn LeRoy, Dick Powell—and Robert Taylor. The word of mouth of this service recruited other clients and soon Ivy was helping with the business and in this capacity got to know Bob and Barbara Stanwyck. The relationship that Ivy forged with Bob would last for the rest of his life. Eventually, Ivy would lose Len to a brain tumor and Bob would bring her on as his private secretary, “even though he typed better than I did!” And she would also become godmother to Bob’s first child, his son Terry. Ivy offers an insight into the deteriorating Taylor-Stanwyck marriage.

She says that Barbara became very jealous of Bob, especially of his weekends away with the guys flying and hunting. She was jealous of friends Bob met and kept in touch with in the Navy, Ralph Crouse (who he would arrange a job for at MGM as his pilot) and Tom Purvis. It got so bad that when either one would call the house, Barbara, if she answered first, would tell Bob, “Your wife is on the phone.”

One day Ivy was discussing Len’s deteriorating condition with Stanwyck. “Len is very confused these days,” she told her. “So am I,” Barbara replied. “I can’t understand Bob’s behaviour. He's gone off the rails. Barbara began to drink quite a bit during this period of time. “It was a very tense relationship,” Ivy recalls. “Barbara would drink a great deal of champagne and would become a different person.” It was at times like this that Barbara would even lash out at Ivy. “She would insinuate that something was going on between me and Bob. Of course it wasn’t. She was just looking for any excuse she could because Bob had lost any desire he may have had at one time for her.” Barbara began to assault Bob’s masculinity. Perhaps it was a defense mechanism to help deal with the fact that Bob apparently didn’t find her attractive sexually any longer. Arlene Dahl was actually happy when she heard that Bob and Barbara had broken up. “I was hoping they would. He was too good of a man to waste on a woman like her.” -"Robert Taylor: A Biography" (2010) by Charles Tranberg

Although the movie would be inconceivable without Fonda, "The Lady Eve” is all Stanwyck's; the love, the hurt and the anger of her character provide the motivation for nearly every scene, and what is surprising is how much genuine feeling she finds in the comedy. Watch her eyes as she regards Fonda, in all of their quiet scenes together, and you will see a woman who is amused by a man's boyish shyness and yet aroused by his physical presence. At first she loves the game of seduction, and you can sense her enjoyment of her own powers. Then she is somehow caught up in her own seduction. There has rarely been a woman in a movie who more convincingly desired a man. Preston Sturges wrote the screenplay specifically for Stanwyck. Source: www.rogerebert.com

Barbara Stanwyck on performing her favorite role, Stella Dallas in "Stella Dallas" (1937): "The task was to convince audiences that Stella's instincts were fine and noble even though, on the surface she was loud, flamboyant, and a bit vulgar."

Barbara Stanwyck and Mae Clarke, 1927, New York

During the making of Big Time, the studio promised Mae Clarke that great things were going to happen to her. Mae and Barbara met for lunch. Mae talked about 'Big Time'. John Ford was in it as himself, a Hollywood director. During the lunch, Mae felt an inexplicable tension from Barbara, that she couldn’t reach her. Mae sat there “with the dearest friend I’ve ever had,” she said. “There was a constraint between us as though we were strangers.” In New York, Mae and Barbara had been inseparable; they’d shared the same bed, eaten together, worked together. Mae couldn’t understand what was wrong. She felt that if she could “just bridge those silences everything would be all right.” There was nothing else to talk about, so Mae talked about the plans the studio had for her. “The picture didn’t mean half as much to me as getting close to Barbara again. But she didn’t understand. “Barbara thought I was getting 'high-hat'. And all I could think of was that Barbara didn’t want to have anything to do with me. I’m a link that binds her to the past. In New York we were harum scarum kids, madcaps, who did crazy things.” -"A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940" (2013) by Victoria Wilson

“Stanwyck was slim, and remained so over her career. Regardless of the obligations and pressures regarding size and shape for women in Hollywood, or her own needs and desires as an actress and a person, or the occasions within the films that show off her body, Stanwyck rarely advertises a superficial fantasy of feminine appearance. She is too busy exploring the subtlety of interactions.” ―Andrew Klevan, author of Barbara Stanwyck (Film Stars), 2013

"Lots of actresses are getting by with good looks and practically nothing else. And there are other actresses who have brains and no beauty," said director William Wellman. "But when you get beauty and brains together, there's no stopping her – and the best example of that is Barbara."

Barbara later described her transformation: “Only through Willard Mack’s kindness in coaching me, showing me all the tricks, how to sell myself by entrances and exits, did I get by. It was Willard Mack who completely disarranged my mental make-up. The process—like all processes of birth and death, I guess—was pretty damn painful. Especially for him. I got temperamental. The truth is, I was scared. I’d storm and yell that I couldn’t act—couldn’t, and what’s more, wouldn’t. I think I can honestly say that this was my first and last flare-up of temperament, because Mr. Mack—who had flattered and encouraged me— shrewdly reversed his tactics.

One day, right before the entire company, he screamed back at me that I was right, I was dead right. I was a chorus girl, would always be a chorus girl, would live and die a chorus girl, so to hell with me. It worked. I yelled back that I could act, would act, was not a chorus girl—was Bernhardt, Fiske and all the Booths and Barrymores rolled into one.”

“Underneath her sullen shyness,” Frank Capra later wrote, “smoldered the emotional fires of a young Duse, or a Bernhardt. Naïve, unsophisticated, caring nothing about make-up, clothes or hairdos, this chorus girl could grab your heart and tear it to pieces … She just turned it on—and everything else on the stage stopped.” 'Ladies of Leisure' was a great hit, a major step up for Columbia, and it made an instant star of Barbara Stanwyck. Critics raved about this lovely young actress, effusively praising the naturalness and honesty of her acting, her unique voice and her strong presence. Photoplay rhapsodized about “the astonishing performance of a little tap-dancing beauty who has in her the spirit of a great artist… Go and be amazed by this Barbara girl.”

David Manners and Barbara Stanwyck in "The Miracle Woman" (1931), based on the play "Bless You, Sister" by John Meehan and Robert Riskin, directed by Frank Capra

She’d become Capra’s favorite actress and he directed her in three more Columbia dramas. 'The Miracle Woman' (1931) was an initially daring but failed attempt at telling the story of a fraudulent preacher, based on the notorious Aimee Semple McPherson. Barbara delivered a strong performance but the cop-out script sank it. 'Forbidden' (’32) was nothing more than mawkish soap opera worthy of neither of them. 'The Bitter Tea of General Yen' (’32) was a truly strange tale with Barbara as the captive and lover of a Chinese warlord, but casting Swedish Nils Asther as General Yen was pure racial cowardice. None approached 'Ladies of Leisure' in quality or box office success. Barbara always considered William Wellman, Frank Capra and Billy Wilder her favorite directors.

Her final 1939 film was Clifford Odets’ 'Golden Boy'. It had been a high-profile hit on Broadway and the movie version was severely marred by a sappy happy ending that was widely criticized, but Barbara was well received for her unflinching portrait of a hard-edged “dame from Newark” who falls for the young hero. The boy, an extremely demanding role, was played by a very nervous newcomer, William Holden.

It didn’t start out too well. When she got word that he was going to be fired, she threatened to walk off the picture if they did any such thing, and spent every available moment coaching and working with him so he could deliver the performance she knew he was capable of. With her help, 'Golden Boy' made William Holden a star, and every year for the rest of his life he sent her flowers on the anniversary of the film’s starting date.

William Holden and Barbara Stanwyck during the 50th Annual Academy Awards at Dorothy Chandler Pavillion in Los Angeles.

Many years later, when Holden and Stanwyck were introduced together as presenters at the 1978 Academy Awards, he unexpectedly ditched their prepared script, saying instead: “Before Barbara and I present this next award, I’d like to say something. Thirty-nine years ago this month we were working in a film together called 'Golden Boy', and it wasn’t going well because I was going to be replaced. But due to this lovely human being and her interest and understanding and her professional integrity and her encouragement and, above all, her generosity, I’m here tonight.” Surprised and overcome, her eyes filled with tears as she embraced him. In the midst of shooting 'Golden Boy', on May 14, 1939, she and Robert Taylor were quietly married.

'Ball of Fire' (1941) solidified her new glamour girl image, her naturally thin upper lip now enlarged and reshaped with artfully flared lipstick. (She retained this lush-lipped look for the next 15 years.) She was Sugarpuss O’Shea, a leggy, bespangled showgirl tootsie on the lam from the cops, hiding out in a houseful of stodgy professors and falling for the youngest of them (Gary Cooper). Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett wrote the delightful script, Howard Hawks directed, and Barbara’s hyper-energetic performance was a critical and popular triumph, earning her another Oscar nomination.

Bad wig or not, 'Double Indemnity' was a smash, and audiences loved seeing Barbara in that sort of role. She scored her third Oscar nomination, but Gaslight’s weepily sympathetic Ingrid Bergman took home the prize.

Paramount’s 'The Strange Love of Martha Ivers' (1946) was a gleeful return to the shady world of noir, her Martha looking gorgeous—no wig this time—as she killed and schemed her way to her own eventual destruction. She now had no reservations about going the limit and her performance was neurotically succulent and corrupt. With her dancer’s grace, economy of movement and venomous eyes, she was certainly by now the most dangerous woman in movies and the poor saps who got tangled in her web paid a fearsome prize. No, it isn’t so pretty what a dame without pity can do. If 'Double Indemnity' started that engine, Martha Ivers put it into overdrive.

In 1951 Barbara divorced Robert Taylor. His infidelities had become common knowledge and her most passionate fidelity had long been to her profession. In 1954 he married German-born actress Ursula Thiess and the following year she gave birth to a son, his first child. Barbara never remarried.

The American Film Institute honored her on April 9, 1987, with AFI’s Salute to Barbara Stanwyck, an all-star tribute to her body of work on film. She had recently thrown her back out and was hospitalized and in considerable pain, but worked out with barbells to be able to be there. A host of her co-stars and admirers lavished their praise, but Billy Wilder topped them all:

“I learned many years ago never to say, ‘This is the best actor or actress I’ve ever worked with,’ because the next time you want a star, he or she is gonna say ‘Wait a minute, you said Stanwyck was the greatest, now what does that make me?’ Always say she’s one of the two greatest stars you’ve worked with and whenever you approach a star, say, ‘You were the one I meant.’ Except, of course, for tonight. I hope nobody’s watching me. She was the best!” When, at the conclusion, Barbara approached the podium to accept accept her award, her response to all the evening’s hosannas was “Honest to God, I can’t walk on water.” In thanking all those who helped her on her journey, she singled out Wilder, “who taught me to kill.” After the evening’s festivities she returned to the hospital.

Rex Reed had once asked her to analyze her stardom or some such folderol, but she didn’t take the bait: “What the hell. Whatever I had, it worked, didn’t it?” -"Barbara Stanwyck: The Furies" (2004) by Ray Hagen from "Killer tomatoes: fifteen tough film dames" by Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner.

"Trusty, dusky, vivid, true, With eyes of gold and brambledew, Steel-true and blade-straight, The great artificer made my mate." —Robert Taylor on Barbara Stanwyck, quoting Robert Louis Stevenson

Ivy Pearson-Mooring would often come over to the Taylor home and do the ironing. Ivy recalls Stanwyck as, “very nice to me, but it was clear that there were problems in their marriage.” Ivy Pearson-Mooring's husband Len Pearson started a business as a valet to the stars. In this capacity he would organize their wardrobe, shine their shoes and press their suits. He soon had a clientele that included Keenan Wynn, Mervyn LeRoy, Dick Powell—and Robert Taylor. The word of mouth of this service recruited other clients and soon Ivy was helping with the business and in this capacity got to know Bob and Barbara Stanwyck. The relationship that Ivy forged with Bob would last for the rest of his life. Eventually, Ivy would lose Len to a brain tumor and Bob would bring her on as his private secretary, “even though he typed better than I did!” And she would also become godmother to Bob’s first child, his son Terry. Ivy offers an insight into the deteriorating Taylor-Stanwyck marriage.

She says that Barbara became very jealous of Bob, especially of his weekends away with the guys flying and hunting. She was jealous of friends Bob met and kept in touch with in the Navy, Ralph Crouse (who he would arrange a job for at MGM as his pilot) and Tom Purvis. It got so bad that when either one would call the house, Barbara, if she answered first, would tell Bob, “Your wife is on the phone.”

One day Ivy was discussing Len’s deteriorating condition with Stanwyck. “Len is very confused these days,” she told her. “So am I,” Barbara replied. “I can’t understand Bob’s behaviour. He's gone off the rails. Barbara began to drink quite a bit during this period of time. “It was a very tense relationship,” Ivy recalls. “Barbara would drink a great deal of champagne and would become a different person.” It was at times like this that Barbara would even lash out at Ivy. “She would insinuate that something was going on between me and Bob. Of course it wasn’t. She was just looking for any excuse she could because Bob had lost any desire he may have had at one time for her.” Barbara began to assault Bob’s masculinity. Perhaps it was a defense mechanism to help deal with the fact that Bob apparently didn’t find her attractive sexually any longer. Arlene Dahl was actually happy when she heard that Bob and Barbara had broken up. “I was hoping they would. He was too good of a man to waste on a woman like her.” -"Robert Taylor: A Biography" (2010) by Charles Tranberg

Although the movie would be inconceivable without Fonda, "The Lady Eve” is all Stanwyck's; the love, the hurt and the anger of her character provide the motivation for nearly every scene, and what is surprising is how much genuine feeling she finds in the comedy. Watch her eyes as she regards Fonda, in all of their quiet scenes together, and you will see a woman who is amused by a man's boyish shyness and yet aroused by his physical presence. At first she loves the game of seduction, and you can sense her enjoyment of her own powers. Then she is somehow caught up in her own seduction. There has rarely been a woman in a movie who more convincingly desired a man. Preston Sturges wrote the screenplay specifically for Stanwyck. Source: www.rogerebert.com

Barbara Stanwyck on performing her favorite role, Stella Dallas in "Stella Dallas" (1937): "The task was to convince audiences that Stella's instincts were fine and noble even though, on the surface she was loud, flamboyant, and a bit vulgar."

Johnny Eager: Robert Taylor's Filmic Redemption

Johnny Eager (played by Robert Taylor) earns his living as a cab driver by day but, on a closer look, he’s a gangster by night who talks to everyone (mostly to dames) with a vaguely disdainful chivalry, even to his parole officer Verne. Two sociology students, Lisbeth Bard (played by a sumptuous Lana Turner) and her friend visit Verne researching for a sociology study and Lisbeth gets especially interested in the “rehabilitated” ex-con Johnny Eager. At first sight, she’s surprised by Johnny’s elegant demeanor and good looks. Sadly, Lisbeth’s father turns out to be District Attorney John Benson Farrell (Edward Arnold), the same man who sent Johnny to jail a few months ago.

As the film advertising claimed “T'N'T burn up the screen in a sizzling romance”, an actual attraction is lit between Johnny & Lisbeth and between Taylor and Turner in real life (the mere sound of Lana’s voice saying “good morning” made Taylor “melt”). Lisbeth is oblivious to the fact Johnny’s leaving a double life and is involved in an operation to reopen the Algonquin dog track – which Lisbeth’s father has threatened with closure. Johnny and Lisbeth continue their clandestine affair behind her fiancé’s back while Farrell insists on unmasking the evil nature percolating beneath Eager’s suave façade.

As if there were not enough shady characters in town who would like to give Eager a .38 lead dose, a rival gang manages to enlist Eager's henchman Lew Rankin in a twist of betrayal. During the early ’40s, the United States had experienced a series of social changes that reflected on the noir subgenre, invoking a more pessimistic portrait than the previous nostalgic gangster pictures from 1930s. Johnny Eager‘s director Mervyn LeRoy (who had filmed top-notch crime dramas as 'Little Caesar', 'Five Star Final', 'Three on a Match'. or 'Hard to Handle') achieves a superior tale of redemption enhanced by Harold Rosson’s shimmering lighting.

Robert Taylor on the set of "Johnny Eager" with director Mervyn LeRoy, 1941

Robert Taylor specifically asked to play the cold-blooded hood in the title role, since he was very impressed by the script, based on a short story by James Edward Grant and John Lee Mahin’s screenplay. Van Heflin plays Johnny’s only real friend, an alcoholic writer who spouts philosophical ramblings, comparing Lisbeth with Cyrano de Bergerac’s Roxane. Although Van Heflin won the Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his poignant performance as Jeff Hartnett, a tormented drunkard who has established a suspiciously intimate bond with Johnny, Robert Taylor’s biographer Charles Tranberg contends ‘this is Taylor’s picture.’

One of the reasons Taylor impacts so deeply on the viewer is the irresistible blend Johnny’s character projects of a misogynist emotional naïvety (showed in his scenes with moll Garnet, played by Patricia Dane) and paradoxically a harrowing need to decipher the meaning of true love (exposed in his revealing interaction with prior girlfriend Mae Blythe). Mae (Glenda Farrell) asks him a favor for old times’ sake, that is Johnny use his influences to relocate her husband -policeman Joe Aganovsky- back to his old precinct. Then Johnny remembers when Mae was his sweetheart in Miami and she was the only dame he’d slug a man over. Seconds later, Johnny’s heart seems to stop in cold blood and he denies her help, in realising Aganovsky is the Agent 711 (a honest cop who was transferred because he would not accept any bribe from the rackets).

“You don’t even know what I’m talking about”, are Mae’s heartbreaking last words to Johnny, when he sardonically needles her about love and old times. These interludes infuse the film’s tone with a relentless pace until the moment we'll end up wondering about Johnny’s doomed destiny. Also, Mae's scene will eventually manifest its value of justice poetic at the last minute.

Precisely, despite of the melodramatic resonance of Taylor’s scenes shared with Turner and Van Heflin, I consider Johnny’s rencounter with Glenda Farrell (Mae Blythe) the best act in the film. Robert Taylor and Glenda Farrell were habitués in Mervyn LeRoy's films: Glenda, beside having played the female lead in 'Little Caesar', had appeared in 'I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang', 'Heat Lightning', 'Hi Nellie!' and 'Three on a Match'. Robert Taylor, in addition to 'Johnny Eager', would work with LeRoy in 'Escape', 'Waterloo Bridge', and 'Quo Vadis'.

On December 8, 1941 United States declared war upon Japan in response to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. 'Johnny Eager' was released in theatres on 9 December 1941. As Charles Tranberg remarks in his biography, Robert Taylor made a contribution to the war effort by donating his monoplane, which was given to the Los Angeles Sheriffs Air Squadron in 1942. The war accelerated the longstanding trend in social stigma of illicit romances, they were nonetheless validated on-screen.

Robert Taylor (despite of having being labeled in his early career as a matinée idol) proves in 'Johnny Eager' he could play perfectly an obscure racketeer, an outlaw who continues to pull off tricks even against his own integrity, and whose aspirations weren’t too different from his film audience’s. The film, a romantic MGM noir thankfully free of the ambigous morality through which modern cinema tries to justify or condemn a defiant character, flows in a cynical (at times sentimental) fashion, and in the end we just want Johnny redeemed in the dark yet relucent streets although his individuality suffers definitively for it.

Article first published as Movie Review: ‘Johnny Eager’: Robert Taylor’s Filmic Redemption on Blogcritics

As the film advertising claimed “T'N'T burn up the screen in a sizzling romance”, an actual attraction is lit between Johnny & Lisbeth and between Taylor and Turner in real life (the mere sound of Lana’s voice saying “good morning” made Taylor “melt”). Lisbeth is oblivious to the fact Johnny’s leaving a double life and is involved in an operation to reopen the Algonquin dog track – which Lisbeth’s father has threatened with closure. Johnny and Lisbeth continue their clandestine affair behind her fiancé’s back while Farrell insists on unmasking the evil nature percolating beneath Eager’s suave façade.

As if there were not enough shady characters in town who would like to give Eager a .38 lead dose, a rival gang manages to enlist Eager's henchman Lew Rankin in a twist of betrayal. During the early ’40s, the United States had experienced a series of social changes that reflected on the noir subgenre, invoking a more pessimistic portrait than the previous nostalgic gangster pictures from 1930s. Johnny Eager‘s director Mervyn LeRoy (who had filmed top-notch crime dramas as 'Little Caesar', 'Five Star Final', 'Three on a Match'. or 'Hard to Handle') achieves a superior tale of redemption enhanced by Harold Rosson’s shimmering lighting.

Robert Taylor on the set of "Johnny Eager" with director Mervyn LeRoy, 1941

Robert Taylor specifically asked to play the cold-blooded hood in the title role, since he was very impressed by the script, based on a short story by James Edward Grant and John Lee Mahin’s screenplay. Van Heflin plays Johnny’s only real friend, an alcoholic writer who spouts philosophical ramblings, comparing Lisbeth with Cyrano de Bergerac’s Roxane. Although Van Heflin won the Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his poignant performance as Jeff Hartnett, a tormented drunkard who has established a suspiciously intimate bond with Johnny, Robert Taylor’s biographer Charles Tranberg contends ‘this is Taylor’s picture.’

One of the reasons Taylor impacts so deeply on the viewer is the irresistible blend Johnny’s character projects of a misogynist emotional naïvety (showed in his scenes with moll Garnet, played by Patricia Dane) and paradoxically a harrowing need to decipher the meaning of true love (exposed in his revealing interaction with prior girlfriend Mae Blythe). Mae (Glenda Farrell) asks him a favor for old times’ sake, that is Johnny use his influences to relocate her husband -policeman Joe Aganovsky- back to his old precinct. Then Johnny remembers when Mae was his sweetheart in Miami and she was the only dame he’d slug a man over. Seconds later, Johnny’s heart seems to stop in cold blood and he denies her help, in realising Aganovsky is the Agent 711 (a honest cop who was transferred because he would not accept any bribe from the rackets).

“You don’t even know what I’m talking about”, are Mae’s heartbreaking last words to Johnny, when he sardonically needles her about love and old times. These interludes infuse the film’s tone with a relentless pace until the moment we'll end up wondering about Johnny’s doomed destiny. Also, Mae's scene will eventually manifest its value of justice poetic at the last minute.

Precisely, despite of the melodramatic resonance of Taylor’s scenes shared with Turner and Van Heflin, I consider Johnny’s rencounter with Glenda Farrell (Mae Blythe) the best act in the film. Robert Taylor and Glenda Farrell were habitués in Mervyn LeRoy's films: Glenda, beside having played the female lead in 'Little Caesar', had appeared in 'I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang', 'Heat Lightning', 'Hi Nellie!' and 'Three on a Match'. Robert Taylor, in addition to 'Johnny Eager', would work with LeRoy in 'Escape', 'Waterloo Bridge', and 'Quo Vadis'.

On December 8, 1941 United States declared war upon Japan in response to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. 'Johnny Eager' was released in theatres on 9 December 1941. As Charles Tranberg remarks in his biography, Robert Taylor made a contribution to the war effort by donating his monoplane, which was given to the Los Angeles Sheriffs Air Squadron in 1942. The war accelerated the longstanding trend in social stigma of illicit romances, they were nonetheless validated on-screen.

Robert Taylor (despite of having being labeled in his early career as a matinée idol) proves in 'Johnny Eager' he could play perfectly an obscure racketeer, an outlaw who continues to pull off tricks even against his own integrity, and whose aspirations weren’t too different from his film audience’s. The film, a romantic MGM noir thankfully free of the ambigous morality through which modern cinema tries to justify or condemn a defiant character, flows in a cynical (at times sentimental) fashion, and in the end we just want Johnny redeemed in the dark yet relucent streets although his individuality suffers definitively for it.

Article first published as Movie Review: ‘Johnny Eager’: Robert Taylor’s Filmic Redemption on Blogcritics

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Robert Taylor: Magnificent Obsession

Barbara Stanwyck had seen Robert Taylor in 'Magnificent Obsession' and 'Broadway Melody of 1936', admired his work, and told him so. 'Magnificent Obsession' was the John Stahl picture from Lloyd C. Douglas’s best-selling novel. In it Taylor was the selfish rich boy who becomes a great doctor in order to care for the woman —Irene Dunne— he accidentally blinds in a drunken selfish state and whom he comes to adore.

Taylor saw Irene Dunne, then thirty-seven years old, as “dignified.” He had “felt the strength of her great experience” and said that her “confident poise could not fail to help anyone with whom she played.” Taylor’s assurance, agility, and depth surprised critics. Women by the hundreds of thousands were fantasizing about Robert Taylor as the dream combination — the perfect lover (full of spirit and play, cocky but not rough) and husband (knowing, presentable, steady, caring).

Robert Montgomery’s world-weary sophistication seemed acidic and faded next to Taylor’s openness and purity. Lloyd C. Douglas’s novel ('Magnificent Obsession', 1929) was brought to John Stahl’s secretary by Joel McCrea, who was tested for the part with Rosalind Russell. The director felt that neither actor was right and instead cast Robert Taylor and Irene Dunne. Following the release of 'Magnificent Obsession' thousands of fan letters were delivered to Metro addressed to Robert Taylor written by women across the country, until ten thousand letters were arriving each week.

'Magnificent Obsession' was a sellout and played to held-over business, as did Taylor’s next picture, Broadway Melody of 1936, from the Moss Hart story “Miss Pamela Thorndyke,” in which Taylor danced with the rangy twenty-three-year old Eleanor Powell in her first major picture and sang Nacio Herb Brown’s “I’ve Got a Feelin’ You’re Foolin’” to June Knight. Louella Parsons called Taylor the most promising actor of the moment.

Hedy Lamarr had been named Glamour Girl of 1938, called the “Dream Girl of 50 Million Men,” all on the basis of one picture, Algiers, made on loan-out to Walter Wanger and United Artists. Lamarr, while shooting Lady of the Tropics , taught Bob how to kiss more convincingly for the cameras. “His usual kiss seemed much more like a school-boy’s when photographed in close-up,” she said. The picture was directed by Jack Conway, Bob’s frequent coyote-hunting partner, and written by Josef von Sternberg, Jules Furthman, Dore Schary, John Lee Mahin, and Ben Hecht, with Hecht getting final screenplay credit.

Barbara and Bob, soon after they met, were one night looking up at a marquee of the Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. Taylor’s name was in lights for the first time —"Robert Taylor And Loretta Young" in 'Private Number', with his name first. Bob was impressed with it all. “Don’t let it go to your head,” said Barbara. “Loretta has been working for years to get her name up there; you’ve been at it for six months. The trick is to keep it up there.” She believed that Flaubert’s observation to de Maupassant about writing was true about acting: “Talent is long patience.”

While shooting 'Waterloo Bridge' (1940), LeRoy got the flu and was laid up for five days. Woody Van Dyke stepped in. Bob was working late and asked Barbara to visit him on his set. She had never been on one of Bob’s sets. She hesitated and said, “Miss Leigh might not like it.” Bob assured her that Vivien wasn’t like that, that it would be fine. Barbara agreed to have Bob drive her onto the Metro lot. She had Bob park his car a short distance from the soundstage where he was shooting. At the last minute Barbara thought it better for her to stay in the car and read a book while Bob worked. -"A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940" (2013) by Victoria Wilson

Taylor told Louella Parsons that he considered "Bataan" (1943) one of his four personal favorite pictures of those he made. The other three were Magnificent Obsession, Waterloo Bridge and Johnny Eager.

Robert Taylor had an old-fashioned appreciation for women. He was courtly and very much a gentleman who had an idealized view of the type of woman he was attracted to. "I couldn’t care for a woman who didn’t respect herself, who didn’t have a passionate desire for making the most of life. It is easy for a girl to be ordinary; that demands no will at all. [...] I’ve invariably been drawn to women who are tolerant, who are good sports. I’m not above relishing a dash of glamour, but to me glamour is not bleached hair and plucked eyebrows and gobs of make-up. It’s that intangible understanding and sweetness that only the woman who has a first-rate heart has. Artificial girls bore me.”

Since the break-up with Barbara, Bob was staying busy with picture making. He was also re-establishing himself as a potent box-office star at the studio. Bob was about to start a film which meant a great deal to him and would team him with one of his favorite leading ladies, Eleanor Parker. The film was 'Above and Beyond', with Bob playing the part of Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets and Parker cast as his wife Lucey. It’s a very human performance in that Bob is playing a man who truly is carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. It may be his all-time best motion picture work.

The chemistry with Parker was strong off screen as well as on. They began an off-and-on affair that would last almost up to the time of Bob’s marriage to actress Ursula Thiess. The affair was an open secret among their friends and at the studio, but they worked assiduously to keep it out of the press. Bob was genuinely fond of Parker, but he never considered marriage. Parker was a take-charge type of woman who wouldn’t let any man dominate her. In too many ways she reminded Bob of Barbara.

Reading the newspaper at his Dorchester Suite, in London, one day in 1952, Bob saw a picture that knocked his socks off. It was of a stunningly attractive woman whom the paper dubbed “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World.” Bob couldn’t disagree. He thought she was stunning with her full lips, dark hair, expressive eyes and luscious figure. Her name was Ursula Thiess and Bob definitely wanted to get to know her better. Ursula was born on May 15, 1924, in Hamburg, Germany. Bob was able to locate Ursula thru the help of her agent, Harry Friedman of MCA. Friedman telephoned and told her that Robert Taylor wanted to meet her for dinner and dancing. Bob took Ursula to the Coconut Grove where they met their companions, Harry Friedman and his wife.

She later recalled that what attracted her most to Bob was his, “down-to-earth, unassuming manner and his beautiful, searching eyes, which were the open windows to his incredible sex appeal.” Bob enjoyed introducing his friends to Ursula and showing her the sights of his hometown. Ursula later recalled that his friends “received us with open arms, making me feel reinstated once more as his woman and his love.” The official announcement of their engagement was made on April 30, 1954. “It was the biggest diamond I ever saw,” Ivy Pearson recalled [about Ursula's engagement ring]. “I asked him if it was real!”

In "Party Girl" (1958) Nicholas Ray came to admire Bob’s dedication to his part and growth as an actor: "I saw Taylor working for me like a true Method actor.” One Ray biographer later wrote that Party Girl, “moves effortlessly from action-packed scenes of violence to more meditative and touching sequences that helps the film to surpass its generic origins. Marked throughout both by his [Ray’s] great professionalism and by his feelings of sympathy for his ill-starred lovers, the movie transcends the conventions of the nostalgic gangster picture to become a passionate, involving tale of moral and emotional rebirth.”

Ursula completed Bob. “I’ve never known such complete happiness as I have since I’ve been married to Ursula,” he told Hedda Hopper. “She’s a really attractive woman... She’s so self-sufficient. Nothing seems to upset or worry her. She’s well-adjusted. I’ve never seen her in a situation she was unable to handle in a quiet sort of way.” Ursula had managed to do something that Barbara never did, nor had the inclination to do, she won over Ruth. “Ursula won Bob’s mother over by her kindness, devotion to Bob and wonderful homemaking skills,” accords to Ivy Shelton-Mooring.

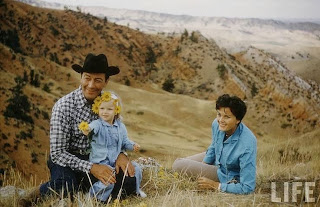

Bob liked the idea of a ranch, especially with an expanding family. He thought it would be a great way for his children to grow up with plenty of time for the out of doors on 113 acres. It also reminded him of his upbringing in rural Nebraska. His daughter Tessa was named after the character from the book 'Tess of the Storm Country', which Bob had read as a child. “Bob’s attitude had taken a complete turn,” recalled Ursula. “While he was reticent to even touch his son as a small baby, this new little female was overindulged with attention.” He affectionately nicknamed her puss-puss.

The ranch was Bob’s refuge and the place he loved the most. “When I think of Daddy, I think of the ranch,” his daughter Tessa says. “It was a great place to be. A great way to grow up.” Bob liked the fact that Terry and Tessa were growing up on a ranch and finding an appreciation for the outdoors and learning respect for the land and the animals that inhabited it.”

In 1988 the Lion’s Building on the Lorimar Telepictures Lot (formerly the MGM Studio Lot) was renamed as the Robert Taylor Building. In 1990 the building was renamed “The George Cukor Building”. According to director Judy Chaikin, the reason was the days of the blacklist. Ironically, in 1983, Cukor was quoted as saying, “Robert Taylor was my favorite actor. He was a gentleman —that is rare in Hollywood.” -"Robert Taylor: A Biography" (2010) by Charles Tranberg

"Robert Taylor was indeed the best combination of gentleman and actor that ever graced the big screen." -Terry Taylor (Robert Taylor's son)

Taylor saw Irene Dunne, then thirty-seven years old, as “dignified.” He had “felt the strength of her great experience” and said that her “confident poise could not fail to help anyone with whom she played.” Taylor’s assurance, agility, and depth surprised critics. Women by the hundreds of thousands were fantasizing about Robert Taylor as the dream combination — the perfect lover (full of spirit and play, cocky but not rough) and husband (knowing, presentable, steady, caring).

Robert Montgomery’s world-weary sophistication seemed acidic and faded next to Taylor’s openness and purity. Lloyd C. Douglas’s novel ('Magnificent Obsession', 1929) was brought to John Stahl’s secretary by Joel McCrea, who was tested for the part with Rosalind Russell. The director felt that neither actor was right and instead cast Robert Taylor and Irene Dunne. Following the release of 'Magnificent Obsession' thousands of fan letters were delivered to Metro addressed to Robert Taylor written by women across the country, until ten thousand letters were arriving each week.

'Magnificent Obsession' was a sellout and played to held-over business, as did Taylor’s next picture, Broadway Melody of 1936, from the Moss Hart story “Miss Pamela Thorndyke,” in which Taylor danced with the rangy twenty-three-year old Eleanor Powell in her first major picture and sang Nacio Herb Brown’s “I’ve Got a Feelin’ You’re Foolin’” to June Knight. Louella Parsons called Taylor the most promising actor of the moment.

Hedy Lamarr had been named Glamour Girl of 1938, called the “Dream Girl of 50 Million Men,” all on the basis of one picture, Algiers, made on loan-out to Walter Wanger and United Artists. Lamarr, while shooting Lady of the Tropics , taught Bob how to kiss more convincingly for the cameras. “His usual kiss seemed much more like a school-boy’s when photographed in close-up,” she said. The picture was directed by Jack Conway, Bob’s frequent coyote-hunting partner, and written by Josef von Sternberg, Jules Furthman, Dore Schary, John Lee Mahin, and Ben Hecht, with Hecht getting final screenplay credit.

Barbara and Bob, soon after they met, were one night looking up at a marquee of the Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. Taylor’s name was in lights for the first time —"Robert Taylor And Loretta Young" in 'Private Number', with his name first. Bob was impressed with it all. “Don’t let it go to your head,” said Barbara. “Loretta has been working for years to get her name up there; you’ve been at it for six months. The trick is to keep it up there.” She believed that Flaubert’s observation to de Maupassant about writing was true about acting: “Talent is long patience.”

While shooting 'Waterloo Bridge' (1940), LeRoy got the flu and was laid up for five days. Woody Van Dyke stepped in. Bob was working late and asked Barbara to visit him on his set. She had never been on one of Bob’s sets. She hesitated and said, “Miss Leigh might not like it.” Bob assured her that Vivien wasn’t like that, that it would be fine. Barbara agreed to have Bob drive her onto the Metro lot. She had Bob park his car a short distance from the soundstage where he was shooting. At the last minute Barbara thought it better for her to stay in the car and read a book while Bob worked. -"A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940" (2013) by Victoria Wilson

Taylor told Louella Parsons that he considered "Bataan" (1943) one of his four personal favorite pictures of those he made. The other three were Magnificent Obsession, Waterloo Bridge and Johnny Eager.

Robert Taylor had an old-fashioned appreciation for women. He was courtly and very much a gentleman who had an idealized view of the type of woman he was attracted to. "I couldn’t care for a woman who didn’t respect herself, who didn’t have a passionate desire for making the most of life. It is easy for a girl to be ordinary; that demands no will at all. [...] I’ve invariably been drawn to women who are tolerant, who are good sports. I’m not above relishing a dash of glamour, but to me glamour is not bleached hair and plucked eyebrows and gobs of make-up. It’s that intangible understanding and sweetness that only the woman who has a first-rate heart has. Artificial girls bore me.”

Since the break-up with Barbara, Bob was staying busy with picture making. He was also re-establishing himself as a potent box-office star at the studio. Bob was about to start a film which meant a great deal to him and would team him with one of his favorite leading ladies, Eleanor Parker. The film was 'Above and Beyond', with Bob playing the part of Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets and Parker cast as his wife Lucey. It’s a very human performance in that Bob is playing a man who truly is carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. It may be his all-time best motion picture work.

The chemistry with Parker was strong off screen as well as on. They began an off-and-on affair that would last almost up to the time of Bob’s marriage to actress Ursula Thiess. The affair was an open secret among their friends and at the studio, but they worked assiduously to keep it out of the press. Bob was genuinely fond of Parker, but he never considered marriage. Parker was a take-charge type of woman who wouldn’t let any man dominate her. In too many ways she reminded Bob of Barbara.

Reading the newspaper at his Dorchester Suite, in London, one day in 1952, Bob saw a picture that knocked his socks off. It was of a stunningly attractive woman whom the paper dubbed “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World.” Bob couldn’t disagree. He thought she was stunning with her full lips, dark hair, expressive eyes and luscious figure. Her name was Ursula Thiess and Bob definitely wanted to get to know her better. Ursula was born on May 15, 1924, in Hamburg, Germany. Bob was able to locate Ursula thru the help of her agent, Harry Friedman of MCA. Friedman telephoned and told her that Robert Taylor wanted to meet her for dinner and dancing. Bob took Ursula to the Coconut Grove where they met their companions, Harry Friedman and his wife.

She later recalled that what attracted her most to Bob was his, “down-to-earth, unassuming manner and his beautiful, searching eyes, which were the open windows to his incredible sex appeal.” Bob enjoyed introducing his friends to Ursula and showing her the sights of his hometown. Ursula later recalled that his friends “received us with open arms, making me feel reinstated once more as his woman and his love.” The official announcement of their engagement was made on April 30, 1954. “It was the biggest diamond I ever saw,” Ivy Pearson recalled [about Ursula's engagement ring]. “I asked him if it was real!”

In "Party Girl" (1958) Nicholas Ray came to admire Bob’s dedication to his part and growth as an actor: "I saw Taylor working for me like a true Method actor.” One Ray biographer later wrote that Party Girl, “moves effortlessly from action-packed scenes of violence to more meditative and touching sequences that helps the film to surpass its generic origins. Marked throughout both by his [Ray’s] great professionalism and by his feelings of sympathy for his ill-starred lovers, the movie transcends the conventions of the nostalgic gangster picture to become a passionate, involving tale of moral and emotional rebirth.”

Ursula completed Bob. “I’ve never known such complete happiness as I have since I’ve been married to Ursula,” he told Hedda Hopper. “She’s a really attractive woman... She’s so self-sufficient. Nothing seems to upset or worry her. She’s well-adjusted. I’ve never seen her in a situation she was unable to handle in a quiet sort of way.” Ursula had managed to do something that Barbara never did, nor had the inclination to do, she won over Ruth. “Ursula won Bob’s mother over by her kindness, devotion to Bob and wonderful homemaking skills,” accords to Ivy Shelton-Mooring.

Bob liked the idea of a ranch, especially with an expanding family. He thought it would be a great way for his children to grow up with plenty of time for the out of doors on 113 acres. It also reminded him of his upbringing in rural Nebraska. His daughter Tessa was named after the character from the book 'Tess of the Storm Country', which Bob had read as a child. “Bob’s attitude had taken a complete turn,” recalled Ursula. “While he was reticent to even touch his son as a small baby, this new little female was overindulged with attention.” He affectionately nicknamed her puss-puss.

The ranch was Bob’s refuge and the place he loved the most. “When I think of Daddy, I think of the ranch,” his daughter Tessa says. “It was a great place to be. A great way to grow up.” Bob liked the fact that Terry and Tessa were growing up on a ranch and finding an appreciation for the outdoors and learning respect for the land and the animals that inhabited it.”

In 1988 the Lion’s Building on the Lorimar Telepictures Lot (formerly the MGM Studio Lot) was renamed as the Robert Taylor Building. In 1990 the building was renamed “The George Cukor Building”. According to director Judy Chaikin, the reason was the days of the blacklist. Ironically, in 1983, Cukor was quoted as saying, “Robert Taylor was my favorite actor. He was a gentleman —that is rare in Hollywood.” -"Robert Taylor: A Biography" (2010) by Charles Tranberg

"Robert Taylor was indeed the best combination of gentleman and actor that ever graced the big screen." -Terry Taylor (Robert Taylor's son)

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

_NRFPT_02.jpg)

_02.jpg)

_NRFPT_01.jpg)

_14.jpg)

_03.jpg)

_02.jpg)

.jpg)