"I can't wait to be forgotten." -Kay Francis

"I can't wait to be forgotten." -Kay Francis Kay Francis and Miriam Hopkins in "Trouble in Paradise" (1932) directed by Ernst Lubitsch

Kay Francis and Miriam Hopkins in "Trouble in Paradise" (1932) directed by Ernst Lubitsch Kay Francis in "Mandalay" (1934) directed by Michael Curtiz

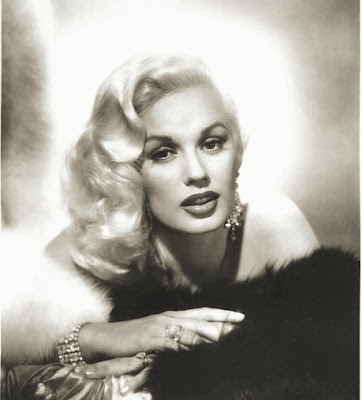

Kay Francis in "Mandalay" (1934) directed by Michael Curtiz Kay Francis, 1936

Kay Francis, 1936 Carole Lombard, Cary Grant and Kay Francis in the film "In Name Only" (1939) directed by John Cromwell

Carole Lombard, Cary Grant and Kay Francis in the film "In Name Only" (1939) directed by John CromwellFor director John Cromwell, Kay was the sentimental choice to play Maida Walker. He had guided Kay to important stardom at Paramount. Carole Lombard had insisted on RKO hiring Kay for the part of the vicious Maida, after jokingly suggesting that Rhea Gable (Clark Gable’s former wife) audition for the role.

Carole and Kay had remained friends since their Paramount days and were particularly tight when Kay was living with Delmer Daves.

Carole and Kay had remained friends since their Paramount days and were particularly tight when Kay was living with Delmer Daves. Daves later reminisced about their fun times with Gable and Lombard: We were all chums. Kay was a free spirit like Carole, and Clark loved women who could make him laugh. Carole would invite Kay and me up to dinner. We’d tell naughty stories and get a little drunk—not really drunk, just high. Then Carole would say ‘Is everybody hungry?’ We’d never move from our chairs! The butler would come out and put a table with folding legs right beside you and serve the soup, then the next course and we’d go on talking and never move. We’d arrive, have drinks, eat, the tables were removed, and then we’d have our brandy and tell funny stories we’d heard on our travels.

Daves later reminisced about their fun times with Gable and Lombard: We were all chums. Kay was a free spirit like Carole, and Clark loved women who could make him laugh. Carole would invite Kay and me up to dinner. We’d tell naughty stories and get a little drunk—not really drunk, just high. Then Carole would say ‘Is everybody hungry?’ We’d never move from our chairs! The butler would come out and put a table with folding legs right beside you and serve the soup, then the next course and we’d go on talking and never move. We’d arrive, have drinks, eat, the tables were removed, and then we’d have our brandy and tell funny stories we’d heard on our travels. Kay Francis’ Maida Walker was one of her most riveting performances and worthy of a best supporting actress nomination. Reaping in accolades must have seemed sweet revenge on Warner Brothers for Kay. The cold and hard-edged temperament she displayed as Maida would have been perfect foil for film noir. However, another distinguished screen role that would take advantage of her unique skills as an actress would not be forthcoming. Kay would add thirteen more features to her credit, and not one of them carried any great impact or significance. It was Hollywood’s loss.

Kay Francis’ Maida Walker was one of her most riveting performances and worthy of a best supporting actress nomination. Reaping in accolades must have seemed sweet revenge on Warner Brothers for Kay. The cold and hard-edged temperament she displayed as Maida would have been perfect foil for film noir. However, another distinguished screen role that would take advantage of her unique skills as an actress would not be forthcoming. Kay would add thirteen more features to her credit, and not one of them carried any great impact or significance. It was Hollywood’s loss. Carole Landis, Martha Raye, Mitzi Mayfair and Kay Francis in 1944

Carole Landis, Martha Raye, Mitzi Mayfair and Kay Francis in 1944 In October 1941, it was announced that Kay would join Ann Sheridan and Olivia de Havilland in the Warners picture Miss Willis Goes to War. Robert Buckner (soon to be Oscar-nominated for Yankee Doodle Dandy) had penned the script. The project never materialized.

In October 1941, it was announced that Kay would join Ann Sheridan and Olivia de Havilland in the Warners picture Miss Willis Goes to War. Robert Buckner (soon to be Oscar-nominated for Yankee Doodle Dandy) had penned the script. The project never materialized. In early 1942, Kay was denying a romantic-linking with actor John Payne. He was seven years her junior. Kay’s first public date with actor Payne was at the California State Guard Military Ball. Kay, along with Constance Bennett and Betty Grable, wore Bundles for Bluejacket uniforms. Kay referred to the affair in her diary as simply, “Horror Ball!” It was the only mention of Payne in her diary.

In early 1942, Kay was denying a romantic-linking with actor John Payne. He was seven years her junior. Kay’s first public date with actor Payne was at the California State Guard Military Ball. Kay, along with Constance Bennett and Betty Grable, wore Bundles for Bluejacket uniforms. Kay referred to the affair in her diary as simply, “Horror Ball!” It was the only mention of Payne in her diary. While Kay was contemplating her future with Erik and making major life decisions, her next screen assignment, Dr. Socrates, underwent a major sex-change. The story, from Collier’s magazine, had been filmed in 1935 starring Paul Muni. As good-guy Dr. Lee Cardwell, nicknamed Dr. Socrates, Muni foiled some notorious gangsters by injecting morphine into their veins. Muni had said the plot was nuttier than a walnut ranch. The story was retreaded at the Foy unit in 1938, re-titled Lady Doctor, and placed Kay in Muni’s shoes.

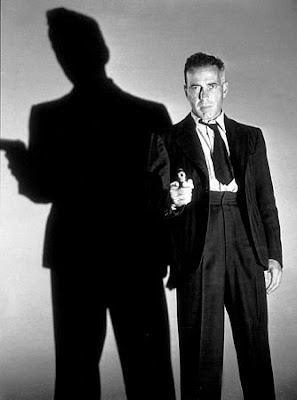

While Kay was contemplating her future with Erik and making major life decisions, her next screen assignment, Dr. Socrates, underwent a major sex-change. The story, from Collier’s magazine, had been filmed in 1935 starring Paul Muni. As good-guy Dr. Lee Cardwell, nicknamed Dr. Socrates, Muni foiled some notorious gangsters by injecting morphine into their veins. Muni had said the plot was nuttier than a walnut ranch. The story was retreaded at the Foy unit in 1938, re-titled Lady Doctor, and placed Kay in Muni’s shoes. Typecast, Humphrey Bogart filled in as the notorious gangster. Kay joined Orry-Kelly to create a variety of tailored suits befitting her call. Filming was touch and go. Vincent Sherman was brought in to create a screenplay on Lady Doctor that could be shot in the twenty days allotted. Sherman got along fine with Kay and thought her a nice lady. He also states in his autobiography, Studio Affairs, that he admired her fortitude during her battle with Jack Warner. Bogart biographers Sperber and Lax pointed out that Kay and Bogart assisted Sherman with the script, “tooling away at the unfinished scenario and trying to make sense of a story about a killer with a Napoleonic complex (Bogart, of course) and a physician (Francis) who subdues him with toxic eye drops. Director Lewis Seiler, a house director with a predilection for glacial pacing, never bothered to consult the script the night before and arrived on the set each morning not quite knowing what to do.

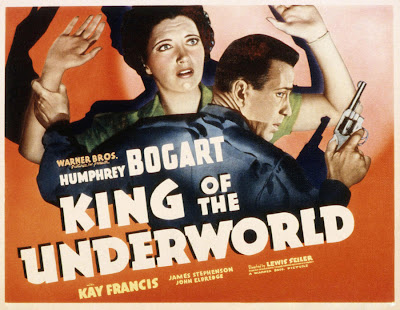

Typecast, Humphrey Bogart filled in as the notorious gangster. Kay joined Orry-Kelly to create a variety of tailored suits befitting her call. Filming was touch and go. Vincent Sherman was brought in to create a screenplay on Lady Doctor that could be shot in the twenty days allotted. Sherman got along fine with Kay and thought her a nice lady. He also states in his autobiography, Studio Affairs, that he admired her fortitude during her battle with Jack Warner. Bogart biographers Sperber and Lax pointed out that Kay and Bogart assisted Sherman with the script, “tooling away at the unfinished scenario and trying to make sense of a story about a killer with a Napoleonic complex (Bogart, of course) and a physician (Francis) who subdues him with toxic eye drops. Director Lewis Seiler, a house director with a predilection for glacial pacing, never bothered to consult the script the night before and arrived on the set each morning not quite knowing what to do. Bogart, whose drawing ticket with the studio was still nebulous at this point, was given star billing for the first time—more out of spite for Kay than anything else. Shortly before the picture’s release in January 1939, the embarrassed Bogart was billed above a new title, King of the Underworld, and Kay, was demoted below the title in much smaller print as a featured player. “It was conceivably the first time that the supporting player drew nine times the salary of the ostensible star. Even the usually cynical industry was stunned, as was the press.”

Bogart, whose drawing ticket with the studio was still nebulous at this point, was given star billing for the first time—more out of spite for Kay than anything else. Shortly before the picture’s release in January 1939, the embarrassed Bogart was billed above a new title, King of the Underworld, and Kay, was demoted below the title in much smaller print as a featured player. “It was conceivably the first time that the supporting player drew nine times the salary of the ostensible star. Even the usually cynical industry was stunned, as was the press.” Bogart’s top-billing was truly a non-achievement and a slap-in-the-face to Kay. Bogart had the added discomfort of having to live up to the impossible task that the ads for the run-of-the-mill feature promised: “Humphrey Bogart blasts his way to stardom!” One must remember that during the filming of King of the Underworld Humphrey Bogart was not the icon we know him today. Far from it. Sperber and Lax felt that by 1939, “the coming decade held little promise for Bogart. He was going nowhere. Duke Mantee was passé.”

Bogart’s top-billing was truly a non-achievement and a slap-in-the-face to Kay. Bogart had the added discomfort of having to live up to the impossible task that the ads for the run-of-the-mill feature promised: “Humphrey Bogart blasts his way to stardom!” One must remember that during the filming of King of the Underworld Humphrey Bogart was not the icon we know him today. Far from it. Sperber and Lax felt that by 1939, “the coming decade held little promise for Bogart. He was going nowhere. Duke Mantee was passé.” Bogart’s character in King of the Underworld was a carbon-copy of the Mantee character Bogart had first portrayed for the Broadway stage in 1935. Director Vincent Sherman commented, “The word was, if it’s a louse-heel, give it to Bogart.” Bogart was used by a studio that repeatedly put him in roles where he was toting a gun.

Bogart’s character in King of the Underworld was a carbon-copy of the Mantee character Bogart had first portrayed for the Broadway stage in 1935. Director Vincent Sherman commented, “The word was, if it’s a louse-heel, give it to Bogart.” Bogart was used by a studio that repeatedly put him in roles where he was toting a gun. In spite of fattening Bogart’s part as gangster (Gurney), the film’s focus still remains on the story of physician Carole Nelson (Kay). She attempts to redeem her career after her husband’s association with Gurney results in his being killed in a police raid. Kay leaves town to hunt down Bogart and gain evidence to prove her innocence. Arriving in Wayne Center (supposed hideout of Bogart and gang), Kay’s reputation had preceded her. The selfrighteous, crotchety local doctor gives Kay flack for being there. “This is a small town ya’ know!” he wails. Kay sizes him up and replies, “With small people in it!” It isn’t long before Bogart shows up at Dr. Kay’s doorstep wounded from a shootout. When he brags about not feeling pain, Kay caters to his unbridled ego. “Some people aren’t sensitive to pain,” she tells him, “especially the moronic type.”

In spite of fattening Bogart’s part as gangster (Gurney), the film’s focus still remains on the story of physician Carole Nelson (Kay). She attempts to redeem her career after her husband’s association with Gurney results in his being killed in a police raid. Kay leaves town to hunt down Bogart and gain evidence to prove her innocence. Arriving in Wayne Center (supposed hideout of Bogart and gang), Kay’s reputation had preceded her. The selfrighteous, crotchety local doctor gives Kay flack for being there. “This is a small town ya’ know!” he wails. Kay sizes him up and replies, “With small people in it!” It isn’t long before Bogart shows up at Dr. Kay’s doorstep wounded from a shootout. When he brags about not feeling pain, Kay caters to his unbridled ego. “Some people aren’t sensitive to pain,” she tells him, “especially the moronic type.” Bogart takes it as a compliment. “Wait’ll I tell the boys!” he crows. “I’m the moronic type!” Humor is really the saving grace of the film, intentional or not, especially when Kay shoves a thermometer in Bogart’s mouth, in front of his gang, and tells him, “Keep your mouth shut!” Bogart, who sees himself as the “Napoleon of Crime,” Humphrey Bogart and Kay, whose ex-spouses had recently married each other, struggled through the filming of Lady Doctor. Kay finds her opportunity to roundup Bogart’s gang when his wound’s infection spreads to his eyes. She claims the highly contagious germ could blind Bogart and his gang. Bogart is miffed. “I gotta get mixed up with some cockeyed germ!” he bellows. Kay puts drops of the liquid “cure” (which creates temporary blindness) into the eyes of Bogart and his boys. Soon the police are surrounding the house and Bogart, as usual, ends up dying on the staircase pleading. “Do me a favor will ya?” he gasps with his last breath, “Don’t tell ‘em that a dame tripped me up!”

Bogart takes it as a compliment. “Wait’ll I tell the boys!” he crows. “I’m the moronic type!” Humor is really the saving grace of the film, intentional or not, especially when Kay shoves a thermometer in Bogart’s mouth, in front of his gang, and tells him, “Keep your mouth shut!” Bogart, who sees himself as the “Napoleon of Crime,” Humphrey Bogart and Kay, whose ex-spouses had recently married each other, struggled through the filming of Lady Doctor. Kay finds her opportunity to roundup Bogart’s gang when his wound’s infection spreads to his eyes. She claims the highly contagious germ could blind Bogart and his gang. Bogart is miffed. “I gotta get mixed up with some cockeyed germ!” he bellows. Kay puts drops of the liquid “cure” (which creates temporary blindness) into the eyes of Bogart and his boys. Soon the police are surrounding the house and Bogart, as usual, ends up dying on the staircase pleading. “Do me a favor will ya?” he gasps with his last breath, “Don’t tell ‘em that a dame tripped me up!” The picture was re-christened King of the Underworld (1939). Bogart felt like a heel taking top-billing from Kay. King of the Underworld was a formula gangster picture with some amusing incidental horseplay by gang members. Such shenanigans probably weren’t too far off the mark. Producer Bryan Foy’s connection with bookies and con men proved resourceful when filming crime pictures. To add some convolution to the storyline, Bogart kidnaps a British author, played by James Stephenson, to co-write his autobiography. Stephenson also adds romantic interest for Kay, which is finally consummated at the film’s finish by the sudden appearance of their seven-year-old child! Bosley R. Crowther, of The New York Times, took the studio to task in his January 7, 1939 review for the film: It never occurred to us that one day we might be the organizer of a Kay Francis Defense Fund. But after sitting through King of the Underworld… in which Humphrey Bogart is starred while Miss Francis, once the glamour queen of the studio, gets a poor second billing, we wish to announce publicly that contributions are now in order… we simply want to go gallantly on record against what seems to us an act of corporate impoliteness.

The picture was re-christened King of the Underworld (1939). Bogart felt like a heel taking top-billing from Kay. King of the Underworld was a formula gangster picture with some amusing incidental horseplay by gang members. Such shenanigans probably weren’t too far off the mark. Producer Bryan Foy’s connection with bookies and con men proved resourceful when filming crime pictures. To add some convolution to the storyline, Bogart kidnaps a British author, played by James Stephenson, to co-write his autobiography. Stephenson also adds romantic interest for Kay, which is finally consummated at the film’s finish by the sudden appearance of their seven-year-old child! Bosley R. Crowther, of The New York Times, took the studio to task in his January 7, 1939 review for the film: It never occurred to us that one day we might be the organizer of a Kay Francis Defense Fund. But after sitting through King of the Underworld… in which Humphrey Bogart is starred while Miss Francis, once the glamour queen of the studio, gets a poor second billing, we wish to announce publicly that contributions are now in order… we simply want to go gallantly on record against what seems to us an act of corporate impoliteness. Among the rich and famous who saw how the studio seized every opportunity to kick her while she was down was Noel Coward. After witnessing the film and her undeserved demotion, Coward pointedly asked Bogart, “Have you and Jack Warner no shame?” Bogart retorted, “None.” Funny, but not very true. Bogart had misgivings about the picture and the way Francis was being treated. While filming a trailer for the picture, Bogart, as gangster Gurney, told of fighting his way to the top in the world of crime. At the finish, he capped his speech saying, “Now I’m King of the Underworld, and nobody is better than I am!” Without missing a beat, Bogart pointed a threatening finger at the camera and sneered, “And that goes for you, too, Jack Warner!”

Among the rich and famous who saw how the studio seized every opportunity to kick her while she was down was Noel Coward. After witnessing the film and her undeserved demotion, Coward pointedly asked Bogart, “Have you and Jack Warner no shame?” Bogart retorted, “None.” Funny, but not very true. Bogart had misgivings about the picture and the way Francis was being treated. While filming a trailer for the picture, Bogart, as gangster Gurney, told of fighting his way to the top in the world of crime. At the finish, he capped his speech saying, “Now I’m King of the Underworld, and nobody is better than I am!” Without missing a beat, Bogart pointed a threatening finger at the camera and sneered, “And that goes for you, too, Jack Warner!” Sperber and Lax, commented on the Francis-Bogart team, saying, "On the set, they were professionals making the best of a bad situation, with Bogart determined to see his costar through the process as quickly and painlessly as possible. They got along well. They also had ex-spouses married to one another." Another bond between Kay and Bogie was their friendship with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louis Bromfield. They often visited Bromfield’s 715-acre home, called Malabar Farm, near Mansfield, Ohio. Kay was a familiar sight at the environmental friendly utopia, carrying pails of milk while wearing her mink coat. During the 1940s Bromfield’s Malabar would play a significant role in both Bogart’s and Francis’ lives.

Sperber and Lax, commented on the Francis-Bogart team, saying, "On the set, they were professionals making the best of a bad situation, with Bogart determined to see his costar through the process as quickly and painlessly as possible. They got along well. They also had ex-spouses married to one another." Another bond between Kay and Bogie was their friendship with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louis Bromfield. They often visited Bromfield’s 715-acre home, called Malabar Farm, near Mansfield, Ohio. Kay was a familiar sight at the environmental friendly utopia, carrying pails of milk while wearing her mink coat. During the 1940s Bromfield’s Malabar would play a significant role in both Bogart’s and Francis’ lives. Malabar was the location for the much publicized marriage of Bogart and Bacall. In 1948, Kay would retreat to Malabar after an unfortunate and scandalous accident.

Malabar was the location for the much publicized marriage of Bogart and Bacall. In 1948, Kay would retreat to Malabar after an unfortunate and scandalous accident. I cannot help but admire Kay Francis as an intelligent, resilient, compassionate, free spirit who loved to laugh and who took her work seriously. I can also see that whatever “weapon” was used against her by Warner Brothers would not have been possible without the puritanical overlay that still burdens the American culture. Instead of blaming Jack Warner for Kay’s “struggle,” maybe we should take a look at ourselves. James Robert Parish noted that “the obituaries for Kay all eulogized her… for her representation of the American woman as a poised, intelligent, and admirable person. However, all marveled at the flood of bitterness that cascaded from the pages of her will, the dammed-up emotion of three decades of hurt.”

I cannot help but admire Kay Francis as an intelligent, resilient, compassionate, free spirit who loved to laugh and who took her work seriously. I can also see that whatever “weapon” was used against her by Warner Brothers would not have been possible without the puritanical overlay that still burdens the American culture. Instead of blaming Jack Warner for Kay’s “struggle,” maybe we should take a look at ourselves. James Robert Parish noted that “the obituaries for Kay all eulogized her… for her representation of the American woman as a poised, intelligent, and admirable person. However, all marveled at the flood of bitterness that cascaded from the pages of her will, the dammed-up emotion of three decades of hurt.” Ultimately, whatever Kay suffered from her mistreatment in Hollywood was simply grist for the mill—and she was smart enough to realize that. But, Kay was human — the greater truth was expressed by Kay herself to British critic W. H. Mooring, when she told him that Warner Brothers “almost broke her heart.” Inevitably, Kay’s Zen-like commentary from her 1933 film Keyhole not only summed up the film, but life as we know it: “Funny thing. We worry and struggle and try to work out our little problems, and then, all of a sudden it’s over.” (She snaps her fingers.) “Just like that! It just doesn’t seem possible.” -"Kay Francis: I Can't Wait to Be Forgotten" (2006) by Scott O'Brien

Ultimately, whatever Kay suffered from her mistreatment in Hollywood was simply grist for the mill—and she was smart enough to realize that. But, Kay was human — the greater truth was expressed by Kay herself to British critic W. H. Mooring, when she told him that Warner Brothers “almost broke her heart.” Inevitably, Kay’s Zen-like commentary from her 1933 film Keyhole not only summed up the film, but life as we know it: “Funny thing. We worry and struggle and try to work out our little problems, and then, all of a sudden it’s over.” (She snaps her fingers.) “Just like that! It just doesn’t seem possible.” -"Kay Francis: I Can't Wait to Be Forgotten" (2006) by Scott O'Brien Notes: Thanks to Laura Wagner, who helped me to receive this fantastic biography of Kay Francis written by Scott O'Brien (published by Bearmanor Media in 2006, 2nd edition in 2007 with a foreword by Robert Osborne). Laura is one of my favorite book reviewers and columnist in Classic Images (www.classicimages.com), I visit her column regularly and I try not to miss any of her Facebook posts, which are thoroughly informative about the stars from the Golden Age, especially I find admirable her work of rescuing the most obscure actors from the silver screen, giving them equal position than the most celebrated ones. Laura is an exhaustive film historian, a superior connoisseur of the early Hollywood and a source of inspiration. I cannot recommend her books enough, vindicating a string of actresses who deserve more of our devotion: "Killer Tomatoes: Fifteen Tough Film Dames" by Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner (2004), "Bride of Golden Images" by Eve Golden and Laura Wagner (2009), "Anne Francis: The Life and Career" by Laura Wagner (2011), and her fabulous deconstruction of biographical tomes - "Let Me Tell You How I Really Feel: The Uncensored Book Reviews of Classic Images' Laura Wagner, 2001-2010" by Laura Wagner and Bob King - this puzzlingly exacting analysis fixes some glaring errors buried amidst pages of praised yet misleading biographies, and it elevates Miss Wagner as one of the few lucid voices in discerning the good authors from the gossip mongers.

Notes: Thanks to Laura Wagner, who helped me to receive this fantastic biography of Kay Francis written by Scott O'Brien (published by Bearmanor Media in 2006, 2nd edition in 2007 with a foreword by Robert Osborne). Laura is one of my favorite book reviewers and columnist in Classic Images (www.classicimages.com), I visit her column regularly and I try not to miss any of her Facebook posts, which are thoroughly informative about the stars from the Golden Age, especially I find admirable her work of rescuing the most obscure actors from the silver screen, giving them equal position than the most celebrated ones. Laura is an exhaustive film historian, a superior connoisseur of the early Hollywood and a source of inspiration. I cannot recommend her books enough, vindicating a string of actresses who deserve more of our devotion: "Killer Tomatoes: Fifteen Tough Film Dames" by Ray Hagen and Laura Wagner (2004), "Bride of Golden Images" by Eve Golden and Laura Wagner (2009), "Anne Francis: The Life and Career" by Laura Wagner (2011), and her fabulous deconstruction of biographical tomes - "Let Me Tell You How I Really Feel: The Uncensored Book Reviews of Classic Images' Laura Wagner, 2001-2010" by Laura Wagner and Bob King - this puzzlingly exacting analysis fixes some glaring errors buried amidst pages of praised yet misleading biographies, and it elevates Miss Wagner as one of the few lucid voices in discerning the good authors from the gossip mongers.